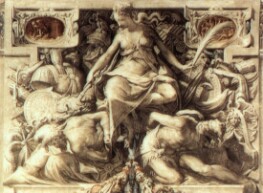

Assumption of the Virgin

This altarpiece by Titian, one of the most inspirational works of Christian art, is undoubtedly among the greatest Renaissance paintings of the Venetian School. The most substantial work of its type in Venice (nearly seven meters high), it was Titian's first major commissioned work in the city and took him two years to paint. It hangs over the high altar in the Franciscan Basilica of S. Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in Venice, where its color and colossal size ensures that it can be seen from the other end of the church.

When it was unveiled in May 1518, it instantly established the young artist as the pre-eminent figure of Venetian art. And it wasn't just its colossal size; it was a revolutionary composition. While earlier religious paintings inside churches (like Giorgione's The Castelfranco Madonna, 1505) had been relatively static, with statue-like saints and regal Madonnas, Titian's figures are bursting with energy and life, thus giving the work enormous emotional power and drama. Its effect on the High Renaissance painting was immediate. When first unveiled, Titian's cinquecento contemporaries were immediately struck by the upward-striving dynamics, the dramatic expressiveness of the scene, and the agitation of the figures. It is perhaps no coincidence that, within 12 months, the mid-air quality and upward motion of the painting were emulated by Raphael in the Transfiguration (c.1518-1520).

Titian divided this exquisite work of Biblical art into three sections. The lowest register represents the terrestrial plane where the disciples witness the assumption; in the middle section, the Virgin Mary soars upward, surrounded by a swarm of angelic cherubim, towards the top part representing Heaven, where God awaits her. The star of the painting is, of course, the Madonna, who is shown as being elevated upwards in a whirl of drapery on solid-looking clouds. Illustrating an essential event in Roman Catholicism - the moment when Mary is assumed into Heaven - it is the most famous Assumption in Renaissance art, if not all Western art. One gets the feeling that she is not just a symbol of salvation but perhaps a symbol of Venice, too. Above the Virgin, the heavenly zone is suffused with golden light (allegedly in homage to the tradition of Venetian mosaic art). At the same time, below her set in shadowy earth, the apostles (Saint Peter, Saint Thomas, and Saint Andrew) are stunned by the miraculous happening but also distraught at losing the mother of Christ, their savior. They implore her to stay, but her gaze is already directed towards Heaven. There, she is awaited by God, who looks with a stern yet sad face on his children below.

Nowadays, Titian is most famous for his vibrant, sensual use of color and his radical technique of painting. Brush loads of color pigments appear to float across the canvas. His virtuoso handling of color is evident in the Assumption: see how the two disciples in the red form a pyramid with the Madonna, drawing our eyes up to the red robe of God. Not long after finishing the Assumption, Titian painted a second large altarpiece in the Frari, known as The Madonna of the Pesaro Family (1519-1526), that is an even better showcase of his exquisite rendering of the luxurious silks and velvets for which Venice was famous. And by moving the image of the Virgin and Child off-center, it again demonstrated the young artist's restless innovation.

In the Assumption, Titian used light and shadow to present the apostles as a mass of bodies rather than highlighting their individuality. This demonstrates the artist's awareness of developments in High Renaissance painting in Florence and Rome and his incorporation of these new ideas into his work. Titian also broke with tradition by omitting all details of the landscape in which the image is situated to focus on the events and emotions of the piece, although the sky above the apostles' heads suggests the setting is outside. The Assumption takes added inspiration from several sources outside Venice. Compositionally, it shares certain iconographical features with the Sistine Madonna (1513) and other works of Raphael, while the vigorous figures of the disciples echo those in Michelangelo's Genesis fresco in the Sistine Chapel. In any event, the painting seems to indicate a clear desire on Titian's part to escape the confines of Venetian painting in order to establish his own universal style of religious art: a style which incorporates power and drama as well as the traditional Venetian appreciation of decorative art and clearly alludes to the coming of Mannerism. The brilliant Venetian neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova described this work as the most beautiful painting in the world. In 1818, it was removed from the altar and transferred to the Venice Academy of Fine Art, where it remained for a century before being returned to the Frari in 1919.