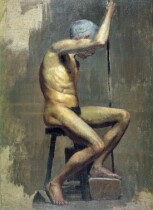

Bull's Head

Original title: Bull's Head

Date: 1942

Art Form: Sculpture

Dimensions: 33.5 X 43.5 cm (13.19 X 17.13 in)

Picasso’s engagement with sculpture was episodic. He would dabble in three dimensions, go back to painting for years at a time, then return to a totally new type of sculpture: wire constructions in the 1930s, ceramics in the 40s, sheet metal follies in the 50s. His dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, is said to have introduced to Picasso the then-novel concept that he might be a “painter-sculptor.” The two disciplines were walled off from one another by different craft traditions, with sculptors requiring training in specific media, like clay and bronze, that Picasso did not have.

Amid Picasso’s constant reinventions, the implication of assemblage took a while to work its way through the system. The most famous of all Picasso’s found-object works hails from 1942. Laboring amid the relative privation of occupied Paris, he grafted a bicycle seat to a set of handlebars, a mythic bull’s head conjured from the detritus of urban life like the face of Jesus radiating from the Shroud of Turin. Bull’s Head was cast in bronze, and what Picasso had to say about that decision is interesting: The marvelous thing about bronze is that it can give the most heterogeneous objects such unity that it’s sometimes difficult to identify the elements that compose it. But that’s also a danger: if you were to see only the bull’s head and not the bicycle seat and handlebars that form it, the sculpture would lose some of its impact. With this quote, Picasso seems to stand at a crossroads between different ways of thinking about art. His sculptures vibrate with the energy of transmissions picked up from everyday material culture, but he is still committed to the ennobling virtues of traditional materials, afraid that these everyday materials won’t add up to much on their own.

As an artist, Picasso will always be associated with painting, and specifically with Cubism, the ur modernist -ism. Yet for all its transformative power, the specific theories of Cubist painting were dated for artists working a generation later, a mode consigned to a previous era of development.

Assemblage, on the other hand, was one of the main events of the century to come. It represented the conceptual innovation necessary for visual artists to adapt to a world of mass-produced industrial objects and ever-more intensive media images. And so, in the light of history, Picasso’s sculpture ends up looking like it has more depth.

.jpg)